| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

1014

DISEASES OF THE APPENDAGES

SYCOSIS VULGARIS

Synonyms.—Sycosis; Non-parasitic sycosis; Folliculitis barbæ; Sycosis cocco-

genica; Acne mentagra; Mentagra; Fr. Sycosis non-parasitaire; Ger. Bartfinne.

Definition.—A chronic inflammatory affection of the hair-fol-

licles of the bearded and mustache regions, due to microbic infection.

As the disease is now known to be microbic, the term non-parasitic,

formerly used to distinguish it from parasitic sycosis or sycosis due to

the ringworm fungus, is no longer applicable.

Symptoms.—The disease may involve only a part of the hairy

region of the face, as, for instance, a portion of the upper lip, especially

just under the nasal orifices, or the entire mustache region; or it may be

more or less limited to the chin or cover the bearded sides of the face;

finally, in extensive cases, the whole surface covered by the mustache

and beard may be involved, and in extreme instances even the eyebrows

also are the seat of the lesions. In my experience the bearded part and

the mustache have appeared of about equal frequency in being the sites

of the eruption. The disease begins, as a rule, slowly, with the appear-

Fig. 253.—Sycosis vulgaris, limited to region immediately under the nose, usually with

a nasal catarrh as the etiologic factor.

ance of a variable number of small red papules or papulopustules or tu

bercles, the most of which, or all, soon become pustular; each lesion is

pierced by a hair. The pustules are small, rounded, or acuminated and

yellowish in color, with but little tendency to spontaneous rupture.

Exceptionally they may remain for the most part papular. At first

they may be quite discrete, later, from the accession of the new lesions,

the affected part becomes quite crowded, and the inflammation is then

usually confluent, with some infiltration and swelling, and beset with

the numerous, small, projecting lesions. At first the hairs remain firmly

seated, but in most cases in the follicles which undergo more pronounced

suppurative action, they loosen and can be readily extracted; and some

follicles may suffer complete destruction. As a rule, however, in spite

of the rather violent aspect of the disease, but comparatively few hairs

are lost, and positive scarring rarely results. When so closely aggregated

that it practically amounts to coalescence, a portion or the entire region

may become crusted, under which there may be a slight tendency to

fungate. There is often a good deal of infiltration and thickening, and

the parts are of a bright or dark-red color, depending upon the type of

SYCOSIS VUIGARIS

1015

inflammatory action. There is, however, no distinct lumpiness or large

cutaneous swellings as in tinea sycosis (ringworm sycosis).

The lesions in some cases, for a time at least, may remain more

or less discrete, and the area of disease may be limited to two or three

small patches; in most instances, however, new lesions arise, form new

aggregations, and, by still further accessions, the areas become confluent

and a large region is involved. The disease may remain somewhat lim

ited, or it may go slowly from worse to worse, involving more and more

of the hairy parts. While it is essentially chronic, the inflammatory

action being of a subacute or sluggish character with sometimes slight

remissions, there are often acute exacerbations.

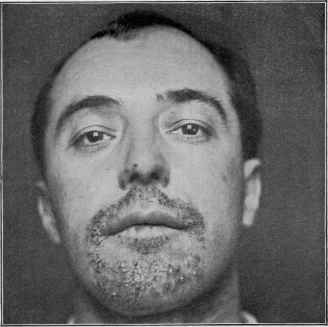

Fig. 254.—Sycosis vulgaris of moderate development, involving chin and to a slight

extent upper lip.

The subjective symptoms are rarely marked or troublesome: there

may be a variable degree of pain and itching and a sense of burning.

In rare instances the disease is limited to the outer portions of the

bearded region, beginning with all the appearances of an ordinary case;

as the process advances it leaves behind a smooth, furrowed, or keloidal

scar, total destruction of the hair-follicles, and permanent loss of hair.

It usually advances in one direction, and, as a rule, with a slightly in

filtrated border. This variety or aberrant form has variously been con

sidered a distinct affection, called lupoid sycosis (Milton), sycosis lupoide

(Brocq), and, finally, and more fully described by Unna,1 under the name

ulerythema sycosiforme.

1 Unna, “Ueber Ulerythema sycosiforme,” Monatshefte, 1889, vol. ix, p. 134.

10l6 DISEASES OF THE APPENDAGES

While sycosis is a disease of the bearded and mustache regions,

and is so understood when the term is used, in exceptional instances

other hairy parts of the body are the seat of similar follicular erup

tion which stops short at the hairy borders; when such occurs, it is, as

a rule, in connection with eczematous eruption elsewhere.

Etiology.—The essential factor of sycosis is microbic; as Bock-

hart1 has demonstrated, the pyogenic cocci (Staphylococcus aureus

and albus) are the usual causative agents, and hence the names sug

gested, sycosis coccogenica, sycosis staphylogenes. In one instance,

presenting the symptoms of ordinary sycosis, Tommasoli2 found that

instead of the usual micro-organisms, a bacillus was the morbific agents

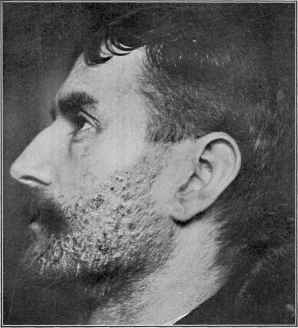

Fig 255-—Sycosis vulgaris, of several years’ duration; involving the entire bearded

region.

and he succeeded, with pure cultures, experimentally in proving this on

himself and rabbits; this discovery led to the variety designation sycosis

bacillogenes.

Accepting the microbic origin, it should be, and indeed probably is

somewhat, though feebly, contagious, although it has never been gen

erally so considered. I have occasionally met with instances in which

the barbershop has apparently been the starting-point, and Brooke3

and others have given evidence of its contagious character. The disease

is, as to be inferred, met with in males only, and usually in those between

1 Bockhart, “Ueber die Aetiologie und Therapie der Impetigo, des Furunkels, und

der Sycosis,” ibid., 1887, vol. vi, p. 450.

2 Tommasoli, “Ueber bacillogene Sykosis,” ibid., 1889, vol. viii, p. 483.

3 Brooke, “The Contagious Nature of Sycosis,” Brit. Jour. Derm., 1889, p. 467.

SYCOSIS VULGARIS

1017

the ages of twenty and fifty. It is not frequent. It is observed in all

walks of life, but is more common among the poor, and especially in those

whose health is impaired. In many cases, it is true, the patients seem in

good condition. Any constitutional disturbance, such as gout, rheuma

tism, dyspepsia, etc, may be of contributory influence.

Local irritation is sometimes of etiologic importance. On the upper

lip, especially the subnasal region, it is often due to the secretion from

a nasal catarrh. Seborrhea is also at times a factor, and occasionally

the disease is observed to follow an eczema of the face. Shaving has been

suggested as a factor, but inasmuch as this procedure is often a necessary

part in the cure of the malady, it can scarcely be considered etiologic

Jackson1 has observed that those whose occupation is in close dusty

rooms, and those in a poor condition of health, furnish the largest number

of cases. The disease has its seat essentially upon the bearded and mus

tache regions, but occasionally the eyebrows share in the eruption. I

have met with one instance in which the scalp and hair-follicles of the

forearms and dorsal surfaces of the fingers were all involved, presenting

the exact symptomatology of the disease as observed on its usual site—

follicular, and stopping at the edge of the hairy skin; this was typically

• shown on the backs of the hands and fingers, intervening hairless parts

being entirely free. The cause of ulerythema sycosiforme is not known—

probably an ordinary sycosis with an added infective factor.

Pathology.—The micro-organisms gaining access give rise to

the inflammatory changes and the clinical manifestations. It can be

readily understood how the process, starting at one point, can soon

involve neighboring follicles by continuous and repeated inoculation.

Tommasoli’s findings indicate that there may be other organisms than

the usual pyogenic cocci. The pathology and pathologic anatomy

have been especially studied by Wertheim,2 Robinson,3 and Unna,4

whose conclusions, while at variance in minute details, are, in their

essential characters, the same. The disease is primarily a perifollicu-

litis, the follicles and their sheath becoming rapidly involved secondarily

in the inflammatory process. The changes are such as are ordinarily

observed in vascular tissue inflammation resulting from these organisms.

The hair-papilla is, as a rule, not destroyed, so that hair loss, except in

very chronic and markedly suppurative cases, does not commonly occur.

The resulting pus escapes at the hair-follicle opening, or through the epi

dermis immediately adjacent. Cocci are usually to be seen in abundance.

As Wertheim states, each follicle really becomes a minute abscess. In

ulerythema sycosiforme the hair-follicles and hair-papillæ, the glandular

structures, and the connective tissue are destroyed and give place to

scar tissue.

Diagnosis.—The disease is to be differentiated from eczema,

which it sometimes resembles, and with which, by some authors, it is

thought to be identical. Eczema rarely stops at the border of the hairy

1 Jackson, “Sycosis: A Clinical Study,” Jour. Cutan. Dis., 1889, p. 13.

2 Wertheim, Wiener med. Jahrb., 1861, ii, p. 87.

3 Robinson, N. F. Med. Jour., Aug. and Sept., 1877, and Manual of Dermatology.

4 Unna, Histopathology.

1018

DISEASES OF THE APPENDAGES

region, and the lesions are, with some exceptions, not pierced by hairs;

eczema is apt to involve the entire skin of the affected area, the follicular

implication being secondary: sycosis involves the follicles primarily,

and only later, when closely aggregated, does the inflammation present

a diffused character. When the latter is present and the parts are

crusted, it is usually necessary to remove the crusts and sometimes

allow a few days to intervene before the case is clear; but in sycosis the

follicular involvement becomes again perceptible. Eczema itches,

usually intensely: sycosis rarely does to any degree. A history of chron-

icity, with no tendency to overstep the borderline, and with but little

variability, would point to sycosis.

Tinea sycosis can scarcely be confounded in average or severe cases;

it begins usually as one or several rings, and continues so, with breaking

of the hair, and often their easy extraction; or it begins in this manner,

or as several lumpy nodules, and rapidly invades the subcutaneous

tissues, and then presents large, nodular swellings, on which the hair

may be broken, fall out, or can be readily extracted. Such conditions

are entirely different from the beginning and behavior of sycosis. In

obscure cases the microscope would decide (see Ringworm).

In acne the evident involvement of the sebaceous glands, the scat

tered lesions, as a rule over the face, evolution, and course, with usually

the presence of blackheads, will prevent its being mistaken for sycosis.

Only carelessness could lead to confusion with a syphilitic eruption;

early eruptions of syphilis are generalized, with other corroborative

symptoms, and late syphilodermata are limited, and usually serpiginous

or segmental in outline.

Prognosis.—The disease is obstinate and persistent, with no

tendency to spontaneous disappearance. The duration, extent, and

character of the inflammatory process must all be considered. Under

proper treatment, however, recovery takes place, in moderately devel

oped cases, sometimes within two or three months, but frequently

longer. In extensive involvement the duration of treatment may be

but several months in favorable cases, but this cannot be expected in

most instances—it is usually six months to a year. An opinion as to

the time required in a given case should always be guarded. A good

deal depends upon the patient’s care and perseverance in carrying out

the treatment. The disease often shows a tendency to recurrence.

The hair should not be allowed to grow for months after apparent cure,

shaving being persistently practised, experience teaching that this tends

to prevent relapses.

Ulerythema sycosiforme is extremely rebellious—much more so

than the ordinary sycosis.

Treatment.—The plan of treatment in most instances consists

of external means alone. The state of the general health should, how

ever, be inquired into, and proper treatment instituted to bring it up

to a normal standard. In some cases there is an underlying constitu

tional debility, which, unless corrected, seems to add to the obstinacy

of the disease; in such cases cod-liver oil is an admirable remedy, the

administration of which not infrequently quite perceptibly aids in ob-

SYCOSIS VULGARIS 1019

taining a result from local measures. Such tonics as iron, quinin, and

manganese will at times also apparently have a favorable influence.

Arsenic may be given for its tonic effect, but it has no specific action.

A special value has been claimed for calx sulphurata, given in doses of

from 1/10 to 1/4 grain (0.0065-0.016) three or four times daily, but my

experience with this drug has not been at all favorable. Sodium sal-

icylate in underlying rheumatic state and stomachic and digestive tonics

in dyspeptic cases will be of service. Alcoholic drinks, indigestible foods,

tobacco, excessive coffee or tea-drinking, and indulging in the many

“bromo” compounds now so common—all have a damaging tendency.

The bowels should always be kept free. Nasal catarrh, if present,

should receive attention. The influence of hygienic living and open-air

life and exercise is, without doubt, of value from a therapeutic stand

point. In obstinate and extensive cases, especially where the suppura-

tive factor is pronounced staphylococcic vaccine should be tried—as a

rule, the results are disappointing, but exceptionally its action is of con

siderable help.

In the external treatment the first steps are to clip the hair short,

free the parts from crusting, if present, and reduce the inflammatory

action. If necessary, the crusts can be removed with starch poultices,

but, as a rule, frequent bathing with warm water and soap and the appli

cation of plain petrolatum or cold cream will accomplish this end in a

day or two. Then mild soothing applications are to be made for a few

days until the activity of the inflammatory process is somewhat allayed.

This may be accomplished by means of applications of an ointment of

zinc oxid, of salicylated paste, or, in fact, by means of any of the other

mild ointments or lotions mentioned in the treatment of acute eczema.

As soon as the inflammatory action has been lessened, and, in fact, in

almost all cases from the very beginning, shaving every day or every

second day should be insisted upon as an essential part of the treatment.

This will not be without pain at first, which is by no means unbearable,

but after the first two or three shavings the operation is not especially

painful. It materially aids in rendering the treatment effective and in

shortening the time required for a cure, and this the patient soon recog

nizes himself. I value this so highly that I should decline to treat a

case unless this measure were acceded to. When the follicular inflamma

tion is of a markedly pustular character, and especially if the hair shows

a tendency to loosen, depilation may be practised; this tends to prevent

the permanent destruction of the follicles. As a routine procedure for

the whole diseased area, however, depilation is, in my experience, too

painful a practice to take the place of shaving, and I do not believe of

greater therapeutic value.

In the management of the external treatment of sycosis it is to be

kept in mind that as patients are often obliged to keep to their business,

the applications for the day-time should be scanty in quantity, or such

as do not conspicuously disfigure. The essential part of the treatment

consists in application of antiseptic ointments and lotions. In recent

and slight cases the applications to be described will usually be effective;

in extensive, long-continued, and obstinate cases these are also to be used,

1020

DISEASES OF THE APPENDAGES

but may be supplemented by the Röntgen-ray treatment. The former

will be referred to first. Ordinarily, the plan of making a slight applica

tion in the morning and applying the ointment spread upon linen or lint

as a plaster at night may be adopted; in the milder case the night appli

cations may also consist of simple anointing. In mild and sluggish types

the ointment, more especially at night, is to be gently, but firmly, rubbed

in. When lotions and ointments are used conjointly, the wash is first

dabbed on for a few minutes, allowed to dry, and then the salve is applied.

The parts should be washed once daily with soap and warm or hot water,

in irritable cases using a mild toilet-soap, and in sluggish and obstinate

types occasionally using sapo viridis or the tincture of sapo viridis. There

is no set guide as to the choice of a remedy among those commonly em

ployed; as a rule, in markedly inflammatory cases the use of a saturated

boric acid solution or a mild resorcin lotion, 0.2 to 1 per cent, strength,

followed by a soothing ointment, such as the boric acid ointment or dia

chylon ointment, will be most likely to be well borne. Later other

remedies will usually be demanded. Often enough one remedy will fail

absolutely to influence the disease favorably, or it may benefit for the

first week or two, and then cease to have any favorable effect; in either

event the remedy is then to be set aside and another tried; later a change

back to an application which had previously benefited can sometimes

advantageously be made.

Although occasionally one of the stronger remedies, such as a strong

sulphur ointment, can be used at the start, it is advisable, except in the

very sluggish cases, to begin with mild treatment, such as just mentioned.

A very weak sulphur ointment, 2 to 5 per cent., is, however, a safe begin

ning application. Or mercury oleate can be used, and is often of decided

benefit, prescribed as an ointment of from 20 grains to 1 or 2 drams

(1.3-8.) to the ounce (32.) of ointment base, of equal parts of cold cream

and simple cerate, or, if the quantity of the oleate is large, with all cerate.

Resorcin is commonly used as a lotion conjointly with a mild salve, as

already mentioned, although it may likewise be employed in the form

of an ointment. The strength of the lotion in chronic and sluggish cases

should be from 1 to 10 per cent.; of the ointment, from 5 to 10 per cent.

One of the most valuable external remedies is precipitated sulphur,

employed as an ointment in the strength of from 20 grains to 2 drams

(1.3-8.) to the ounce (32.) of petrolatum or cold cream; in the form of a

lotion, the Vleminckx’s solution applied diluted with from 5 to 15 parts

of water and supplemented with a mild sulphur or a boric acid salve or

cold cream deserves mention. Owing to its odor, this lotion is not a

pleasant remedy, and should be used only when other treatment has

proved unsuccessful. Hays has also found it of service. A compound

ointment as follows has been especially useful in some cases:

R. Sulphuris præcipitati, 3j (4.);

Balsami Peruvianæ, 3j (4,);

Unguenti diachyli, 3vj (24.).

It should be made up fresh every week or so, as the color becomes grad

ually darker and the ointment less efficient from chemical change.

SEBORRHEA

I02I

Ichthyol is another valuable remedy in the treatment of sycosis,

employed usually as an ointment in the strength of from \ dram to 2

drams (2.-8.) to the ounce (32.) of petrolatum, cold cream, or simple

cerate. In weakest proportion it is also a safe application for the begin

ning treatment. It may also, conjointly with an ointment, be employed

as an aqueous solution in from 2 to 10 per cent, strength. It may like

wise be used in an ointment of sulphur, with advantage, as follows: R.

Sulphuris præcipitati, 3ss-iss (2.-6.); ichthyol, 3j-iss (4.-6.); petrolati,

q. s. ad 3j (32.). Ehrmann warmly advocates the treatment of this

disease with a 10 per cent, solution of pyoktanin, introduced into the

diseased follicles by cataphoresis—the positive electrode, soaked in this

solution, is applied to the part, and the cathode held in the hand.

The Röntgen-ray treatment is occasionally found a valuable addi

tion to our means of treating this disease, and should be tried in per

sistent, extensive, and obstinate cases. The parts other than those to

be treated should be properly protected with lead foil. It need not be

added that the use of so potent an agent as the x-ray requires caution.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |