| MEDICAL INTRO |

| BOOKS ON OLD MEDICAL TREATMENTS AND REMEDIES |

THE PRACTICAL |

ALCOHOL AND THE HUMAN BODY In fact alcohol was known to be a poison, and considered quite dangerous. Something modern medicine now agrees with. This was known circa 1907. A very impressive scientific book on the subject. |

DISEASES OF THE SKIN is a massive book on skin diseases from 1914. Don't be feint hearted though, it's loaded with photos that I found disturbing. |

vitiligo

Synonyms.—Leukoderma; Leukopathia; Acquired leukasmus; Acquired leuko-

pathia; Acquired achroma; Acquired piebald skin.

Definition.—A disease involving the pigment of the skin alone,

characterized by the development of several or more round, oval, cir

cumscribed, smooth, milky-white patches, tending to increase in size,

and exhibiting at their margin increased pigmentation.

Vitiligo and leukoderma are synonymous and interchangeable terms,

although some authors use the former for the acquired disease and the

latter for the congenital patchy loss of pigment, also designated partial

albinismus.

Symptoms.—In this affection there appear one or more small

round or oval white spots, most frequently primarily on the backs of

the hands, trunk, and face, these being favorite localities. In their earli

est beginning, which, as a rule, is insidious, they are usually unnoticed,

and often they escape observation until they are the size of a pea or

larger. It is not improbable that close inspection would show, in some

cases at least, that the first change was a hyperpigmentation followed by

atrophy of pigment and the development of the characteristic milky-

white spot. They tend to enlarge slowly, the neighboring skin showing

an excess of pigment, usually sufficient in degree to give it a much darker

color than obtains in the normal state. Indeed, in those of white skin

the darkened border is often considered by patients as the pathologic

condition, and the inclosed white areas looked upon merely as integument

not yet affected. In those of darker skin, however, and in negroes, the

change to the milky-whiteness is naturally the more conspicuous.

The spots are smooth on the surface and are not elevated above the level

of the skin, there being no changes other than pigment diminution with

surrounding increase in pigmentation. They vary in size from a scarcely

measurable spot to that of the palm and even larger. Their shape is

usually round or oval, sometimes irregular, owing to the spots becoming

1 Jefferiss, Lancet, 1872, vol. ii, p. 294.

VITILIGO

611

confluent; the edges are always convex, those of the pigmented bordering

skin concave. New spots may form from time to time and coalesce, and

may cover a surface of greater or less extent, forming large white areas

with irregularly rounded or scalloped borders. When such ensues, the

loss of pigment is much less noticeable than the surrounding hyperpig-

mentation. In color they are pinkish-white or dead milky-white. Both

to the touch and sight no difference from the normal skin is to be detected,

and none in reality exists, except that of the pigment changes. Within

the whitened areas the hairs may retain their normal color, but generally

they also share in the pig

mentary loss. The activity

of the sebaceous and sudori

ferous glands is not inter

fered with, and subjective

symptoms are not present.

The malady may be

extremely slight, only a

few spots presenting, or

they may be numerous, and

exceptionally may gradu

ally invade the entire sur

face, as in instances ob

served by Lévi, Hall, Hard-

away, Simon, and myself.1

While the affection shows

a predilection for the dor-

sum of the hand, the face,

neck, and trunk, and also

the genital and perineal re

gion, it may begin or occur

upon any hairy or non-hairy

part2 of the body. Occa

sionally there will be a few

spots on the face and hands

and one or several in the scalp, the latter making themselves known

by the whitening of hair growing thereon. Not an infrequent site

is around the eyes, surrounding them by a white band, which in the

negro produces striking disfigurement. The disease is characterized

by its slow course and by its chronicity, months and sometimes years

elapsing before it reaches conspicuous development. It may, after a

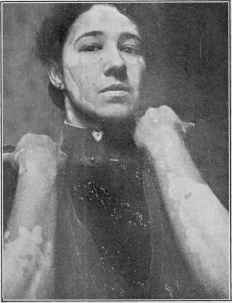

Fig. 144.—Vitiligo; patient a dark brunette

aged thirty; considerable increase in pigmenta

tion beyond the white vitiligo areas.

1 Lévi, “Recherches sur le Vitiligo,” Receuil de Mem. de Méd. de Chir. et de Pharm.

mil., 1865, p. 193 (3 cases); Hall, Louisville Med. News, 1880, vol. x., p. 148, records

the case of a dark mulatto who, with the exception of a part of the chin and a few small

patches on the hands, became completely white; Hardaway, Manual of Skin Diseases,

second edit., p. 280 (2 cases, 1 a white man and 1 a negro, with illustration of the negro,

p. 278); Simon (loc. cit.) noted a few instances of practically general involvement;

Stelwagon, Amer. Jour. Med. Sci., July, 1885 (white man); and Trans. College of

Physicians, Philada., 1894 (negro).

2 In 31 instances noted by Lévi it began on the scalp in 6 cases, epigastric region in

4, forearm in 3, scrotum in 3, breast in 3, ends of the fingers in 2, hands in 2, face in 2,

back in 1, arm in 1, penis in 1, and at the site of scars in 2 (region not stated).

6l2 ATROPHIES

time, remain stationary, and in rare instances retrogresses, but, as a rule,

however, it is progressive, although its increase is often so slow that it is

scarcely perceptible. With some exceptions it can be stated that when

the normal pigment has once been lost, it does not return. When a larger

area has been deprived of its pigment by the coalescence of several or

more patches, and the coalescing hyperpigmented borders may not have

completely disappeared, the brownish islets remaining are taken for the

diseased condition and may lead to errors in diagnosis. Season of the

year has no material influence, if any, upon the morbid process, but

during the summer months the discoloration is more noticeable and

Fig. 145.—Vitiligo; showing also the surrounding hyperpigmentation. A common site

for the patches.

disfiguring, owing to the increase in depth of coloring of the bordering

pigmentation, which is due to the greater action of the actinic rays and

to the direct exposure to the sun, the whitened areas being but slightly,

and usually not at all, influenced. As a result the white looks relatively

more pronounced, the surrounding pigmentation is increased, and the

blemish, in consequence, more noticeable. In women of naturally very

light skin the patches give rise to but little annoyance except during the

sunny season, when, for the reasons stated, they become quite conspicu

ous. Not infrequently, however, considerable disfigurement results

when such regions as the face, neck, and hands are involved, even in the

VITILIGO

613

winter time, and proves a source of much mental worriment. The mal

ady in the negro is, of course, a striking one, and extensive milky-white

surface often results, examples of the disease in this race giving rise to

the occasional newspaper notices of a “negro turning white”; in a few

instances already referred to the change was in reality complete. At

no time during its course is the general health impaired, the malady

having no damaging influence, but, on the other hand, ill health from any

cause is apt to lead to further increase in the patches.

Etiology and Pathology.—The cause of vitiligo is unknown.

Although not common, it is not infrequent. A relationship to disease

of the suprarenal capsules has been suggested (McCall Anderson). It

occurs in males as well as females, and with, usually, about like fre

quency, although of Lévi‘s 37 cases 28 were men. It rarely begins before

the tenth, nor after the thirtieth, year. According to statistics, it is

more frequent in tropical countries (India) and in the dark races. Forel1

states that it is very common in certain districts of Columbia, where

the natives are mostly of mixed negro, Spanish, and Indian blood. , It is

not frequent, but still not at all rare, in our own country. Some observ

ers are of the opinion that extremes of heat and cold both seem of pos

sible etiologic import. At times it is hereditary. It is undoubtedly to be

looked upon as a neurosis, and of more frequent occurrence in neurotic

individuals. Often however, absolutely no history of systemic disturbance

can be obtained. In some instances severe illness, such as ague, scarlatina,

and typhoid fever, would appear to exert an influence. There scarcely

seems a doubt that the nervous system plays an important part, as shown

by the observations of Fèvre, Wyss, Fournier, Schwimmer, Bulkley, and

others.2 Extensive cases resulting after fractures and injuries to nerves

have been reported. It is not infrequently associated with alopecia

areata, and occasionally with morphea. Its occurrence in Graves’

disease has also been noted (Trousseau, Raynaud, Rolland, Bramwell,

Dore, and others).3 The malady has been occasionally observed to

begin at the site of an injury, from pressure, ulcerations, condylomata

lata, and burns. Shepherd has noted the disease in one instance to

start from the pressure of a collar-stud and another from the spots

left after burning warts. Hebra believed that not infrequently the

first area arose in close proximity to a previously existing pigmented

mole. The so-called pigmentary syphilid (q.v.) is thought by some

observers to be a vitiligo (vitiligo syphilitica) starting at the sites of

former macules.4

The very earliest pathologic change to be noted in vitiligo is, I

1 Forel, Munch, med. Wochenschr., 1897, p. 1009.

2 Quoted by Leloir, Twentieth Century Practice, vol. v, p. 848; Lebrun, These de

Lille, 1886, was also of the opinion that other nervous disturbances were usually to be

found.

3 Dore, “Cutaneous Affections Occurring in the Course of Graves’ Disease,” Brit.

Jour. Derm., 1900, p. 353.

4 That syphilis has, however, any etiologic relationship to true vitiligo, as Marie

and some others suggested, seems, in my judgment, without the slightest tangible

foundation. Thibiérge (Annales, Feb., 1905, p. 128), and others give ample negative

evidence, as for example the existence of vitiligo in those whose syphilis is contracted

subsequently.

614

ATROPHIES

believe, an increase of pigment,—a hypertrophy instead of an atrophy,

—followed by diminution or atrophy, and in the further spread of the

lesions the same pathologic steps are gone through. Anatomically, as

to be inferred, the whitish spots are seen to be wholly devoid of coloring-

matter, whereas the surrounding brown discoloration shows hyperpig-

mentation. The atrophy of the terminal nerves noted by Leloir1 and

Chabrier has not, up to the present, been confirmed.

Diagnosis.—The diagnosis is usually not difficult. In extensive

cases, where the pigmented portions are the more striking, it might be

confused with chloasma, but it may be differentiated from the latter by

the fact that the white areas have convex borders, and the pigmented

part would naturally show the reverse,—concave,—while in chloasma

these would be reversed, the chloasma pigmentation being irregularly

round or diffused. Moreover, chloasma, as generally encountered, is

upon the forehead and sometimes on other parts of the face as well,

but it is rare elsewhere. Under the same circumstances it could possibly

be confounded with tinea versicolor, but the same points as regards the

borders would obtain here also, and when it is borne in mind that in

tinea versicolor the patches are usually furfuraceous, of a yellow or fawn

color, and the intervening skin is normal in appearance, no error should

arise; furthermore, the microscope will reveal the presence of the micro-

sporon furfur, the causative agent in the latter malady. Another dis

ease which, upon casual inspection, it resembles to some extent is mor-

phea. The latter, however, is associated with structural changes in the

skin, while in vitiligo there exists only an absence of pigment in circum

scribed patches, and which are on a level with the skin, whereas in mor-

phea the patches may be somewhat elevated above it, or sometimes

slightly depressed, and the seat, as disclosed to the touch, of other

distinct changes. Occurring in tropical climates, it is at times con

founded with the white patches of true leprosy. Indeed, according to

Minch, vitiligo is somewhat widely distributed in Turkestan, and is

considered contagious by the Sarts; affected persons are segregated and

kept with the lepers within special inclosures (Ziegler)—a most extra

ordinary procedure unless, as is possible, they are held as simple sus

pects temporarily. In this type of leprosy, however, the whitish patches

are anesthetic and there are structural changes in the skin and constitu

tional symptoms present, which is not the case in vitiligo. Partial

albinism, which, as already remarked, is often termed leukoderma, is,

reality, similar to this malady except that the normal pigment is absent

from birth; it is, therefore, a congenital condition, whereas vitiligo de

velops during life.

Prognosis and Treatment.—The outlook for recovery from

the malady is not very encouraging. The spots tend, as a rule, to in

crease quite slowly in size for a number of years, and the skin over parts

of the body may become entirely deprived of pigment. In such instances

1 Leloir, “Contribution a l‘Etude des affections cutanées d‘origine trophique,”

Arch, de Physiol., 1881, p. 397; see also interesting clinical and histologic paper by

Marc,“Beiträge zur Pathogenese der Vitiligo und zur Histogenese der Hautpigmen-

tirung” (with review and references), Virchow‘s Archiv, vol. cxxxvi, p. 21.

VITILIGO

615

the last remnants are a few islets of pigmentation, the remains of por

tions of the pigmented borders, which also gradually fade away. Gen

eral involvement is, however, extremely rare. Not infrequently, after

progressing for some years, it comes to a standstill, and exceptionally it

retrogresses and disappears. Fortunately, the disease gives rise to no

symptoms other than the disfigurement.

It is questionable how far treatment influences its course. The con

tinued administration of arsenic, along with tonic remedies, if indicated,

has in some instances, it is believed, influenced it favorably. Duhring

considers this the most valuable remedy, and in some cases under my

care the progress of the malady seemed to be stayed. Pilocarpin has

likewise been suggested, and also thyroid; recently good effects from

suprarenal gland have been claimed. In young patients cure has been

stated to follow the use of potassium bromid internally, along with alka

line baths (Besnier and Doyon). General galvanization and the use of

the battery with the positive electrode to the back of the neck and the

other over the patches has been credited with favorable influence. The

general condition of the patient should receive attention, and measures

directed toward bringing the health up to the normal state adopted. In

recent years I have prescribed most frequently both arsenic and supra

renal gland in this disease, and exceptionally with seeming benefit.

Externally the white patches can be rendered less conspicuous, and

the disfigurement lessened, by reducing the pigmentation of the border

by the means used in the treatment of chloasma. Recently Savill1

successfully employed for this purpose pure phenol, painting it over;

the outer epidermis subsequently exfoliating, with a disappearance of

the discoloration. In cases of sensitive skin it would be advisable to

apply it at first weakened with alcohol, and to limit the application to a

small area. In addition to endeavoring to lessen the bordering pig

mentation, stimulating applications to the white patches, with a view to

producing hyperemia and consequent pigment deposit, can, if thought

advisable, be practised. One of the best for this purpose is the negative

electrode of a galvanic battery, with a current of 2 to 5 milliampères.

It should not be held on the same spot for more than one to several

minutes, so as to produce redness, but to avoid too great effect, otherwise

some damage might be done. The application of the tinsel or metallic

brush, either with the faradic or galvanic battery, and the high frequency

electrode will likewise produce redness. The actinic rays, as well as

heat rays, of the various lamps will also tend to produce pigmentation.

Mustard, in the form of a plaster, cantharides, burning glass, and similar

measures are also resorted to. The white patches may be masked by

coloring, from time to time, with walnut juice or similar stain, or with

an extremely weak tincture of iodin or like substance.

1 Savill, Brit. Jour. Derm., 1898, p. 99.

But first, if you want to come back to this web site again, just add it to your bookmarks or favorites now! Then you'll find it easy!

Also, please consider sharing our helpful website with your online friends.

BELOW ARE OUR OTHER HEALTH WEB SITES: |

Copyright © 2000-present Donald Urquhart. All Rights Reserved. All universal rights reserved. Designated trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our legal disclaimer. | Contact Us | Privacy Policy | About Us |